Many of us are very familiar with the great success story of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine research (particularly the story of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine designed by Reuben College fellow Teresa Lambe). Within an unprecedented short timeframe, several vaccine candidates were developed, approved, and deployed. These vaccines demonstrated high efficacy in preventing severe disease and death. However, there are other vaccine candidates that were not approved for human trials after preclinical (animal) studies.

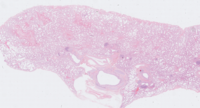

Lung slide from a rhesus macaque that has been stained with Haematoxylin and eosin (H+E), which is used to give an overview of lung damage and immune cell infiltration into lung tissue

My DPhil project, funded by the UK Health Security Agency, focuses on vaccine-associated enhanced disease (VAED), a rarely observed phenomenon whereby vaccination exacerbates disease following infection with the pathogen being vaccinated against. For example, in dengue virus, some antibodies can actually help the virus to invade a particular type of immune cell, which dengue virus has adapted to live within. If a vaccine induces the production of these antibodies, it can help dengue virus to infect these cells and make the disease worse in an infected person. This is called antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) and is one way that VAED can occur. Other forms of VAED have been observed in vaccines against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and measles in the 1960s. There is now an effective licensed vaccine against measles but the concerns around VAED have contributed to the delays in RSV vaccine development.

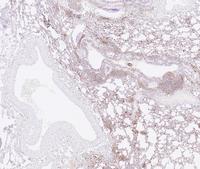

At the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, there were concerns that vaccines developed against SARS-CoV-2 might induce VAED. This was based on some previous studies for vaccines against other coronaviruses, such as SARS (SARS-CoV-1) and Middle-East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which were carried out in various animal models (primarily mice and a species of monkey called the rhesus macaque). Thankfully, this concern was not realized for SARS-CoV-2 in any of the vaccines that went on to be approved for clinical (human) use. As for the vaccine candidates that did not successfully move to human trials, there were no clear-cut cases of VAED in the rhesus macaque, even from a vaccine that was specifically designed to try to induce VAED in macaques so that we could study it further.

Lung slide from a rhesus macaque that was stained for a protein called CD68, which is used to identify a type of immune cell called a macrophage

However, the difference between VAED and vaccine failure is often unclear: if an animal shows signs of moderate or severe lung damage after infection despite being vaccinated, does this mean that the vaccine it was given made the disease worse, or that the vaccine didn’t work very well? Recently, I have published a review article in Frontiers in Immunology which details what we know about previous VAED from both animal and human cases of the phenomenon caused by vaccines against dengue virus, RSV and measles. This article also describes the complicated story of VAED in coronavirus vaccine studies in animals, as mentioned previously. Poor data on lung damage in some of these studies makes the findings difficult to interpret, so there are still questions about the likelihood of VAED in vaccines against coronaviruses. In the discussion section, we describe how new vaccine platforms (viral vectors and mRNA) may be better at avoiding VAED, which might explain the absence of this phenomenon for SARS-CoV-2. We also outline a framework for the investigation of VAED, which we can use to try to answer that important question: VAED or vaccine failure?

During my DPhil project, I will be studying samples from rhesus macaques that were given different types of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine at the UK Health Security Agency at Porton Down in 2020, with the goal of investigating possible VAED in the unsuccessful vaccine candidates. I hope that this research will help to shed light on the poorly-understood mechanisms of VAED, so that we can continue to avoid it when making future vaccines.

Cillian Gartlan is a first-year DPhil student studying vaccine-induced immune responses to high-consequence emerging viruses. He is passionate about science communication and public engagement with research.